Rabbit Hole #4

Money Can Buy Happiness

(in variable and diminishing quantities)

Welcome to Rabbit Hole #4. The Rabbit Hole series offers deep dives into random trading and macro topics that fascinate me. Today I look at the relationship between money and happiness and how your money morals can impact your trading. This write-up is adapted from my book Alpha Trader.

I grew up in a home where money was not plentiful. There was enough money to pay the bills but going out for dinner meant Ponderosa or Frank Vetere’s, and family holidays involved lots of driving and Super 8 motels. Sometimes my mom had to say “no” to a school field trip because it was too expensive. That kind of thing. My early experiences with scarcity (and exposure to financial abundance later in my childhood) are an important part of the adult I am today.

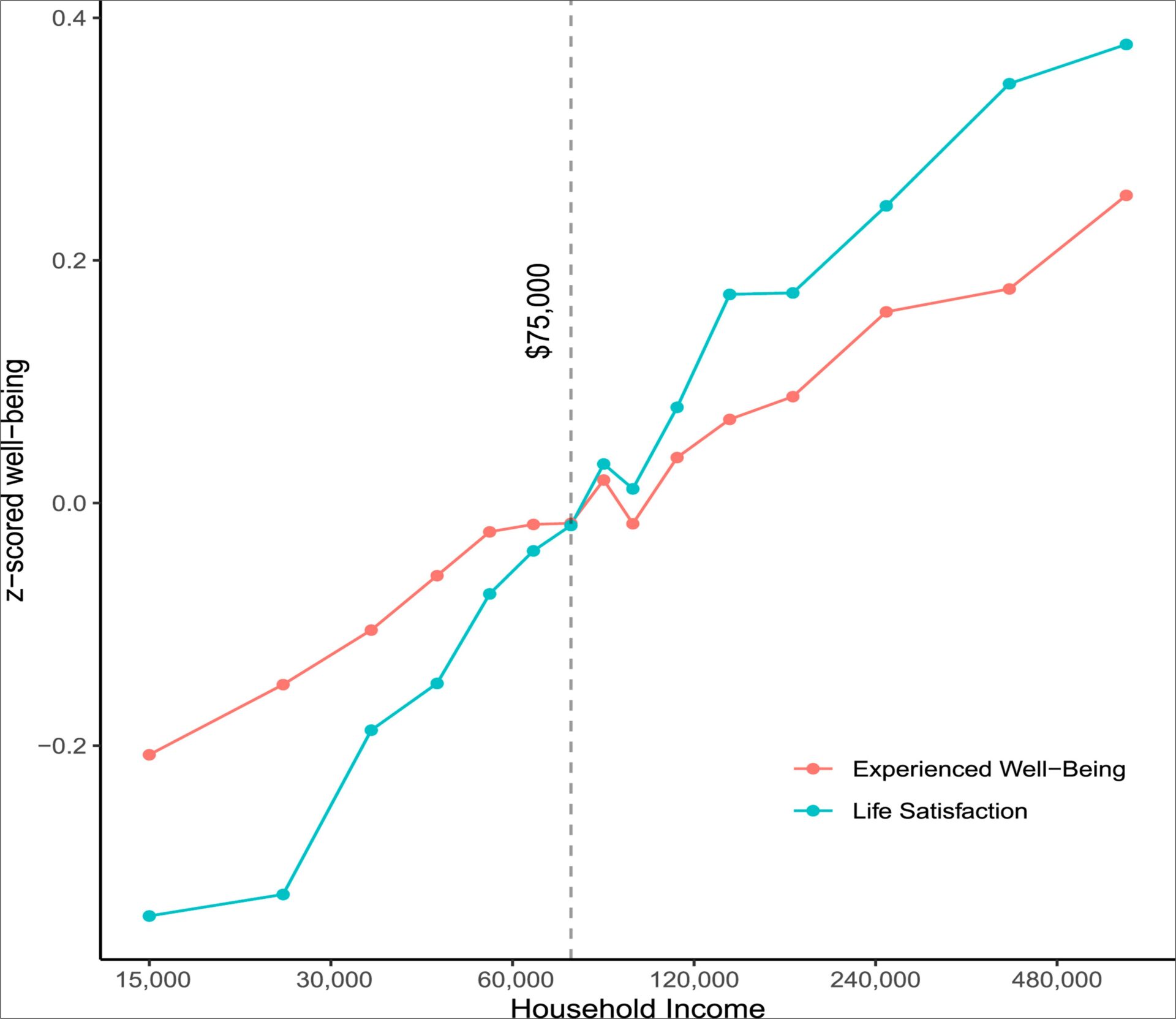

I recently came across some research by Matthew Killingsworth of Wharton which pushes back against conventional wisdom about money vs. happiness. You can read the full paper here. Or a brief summary article here. Here is the abstract:

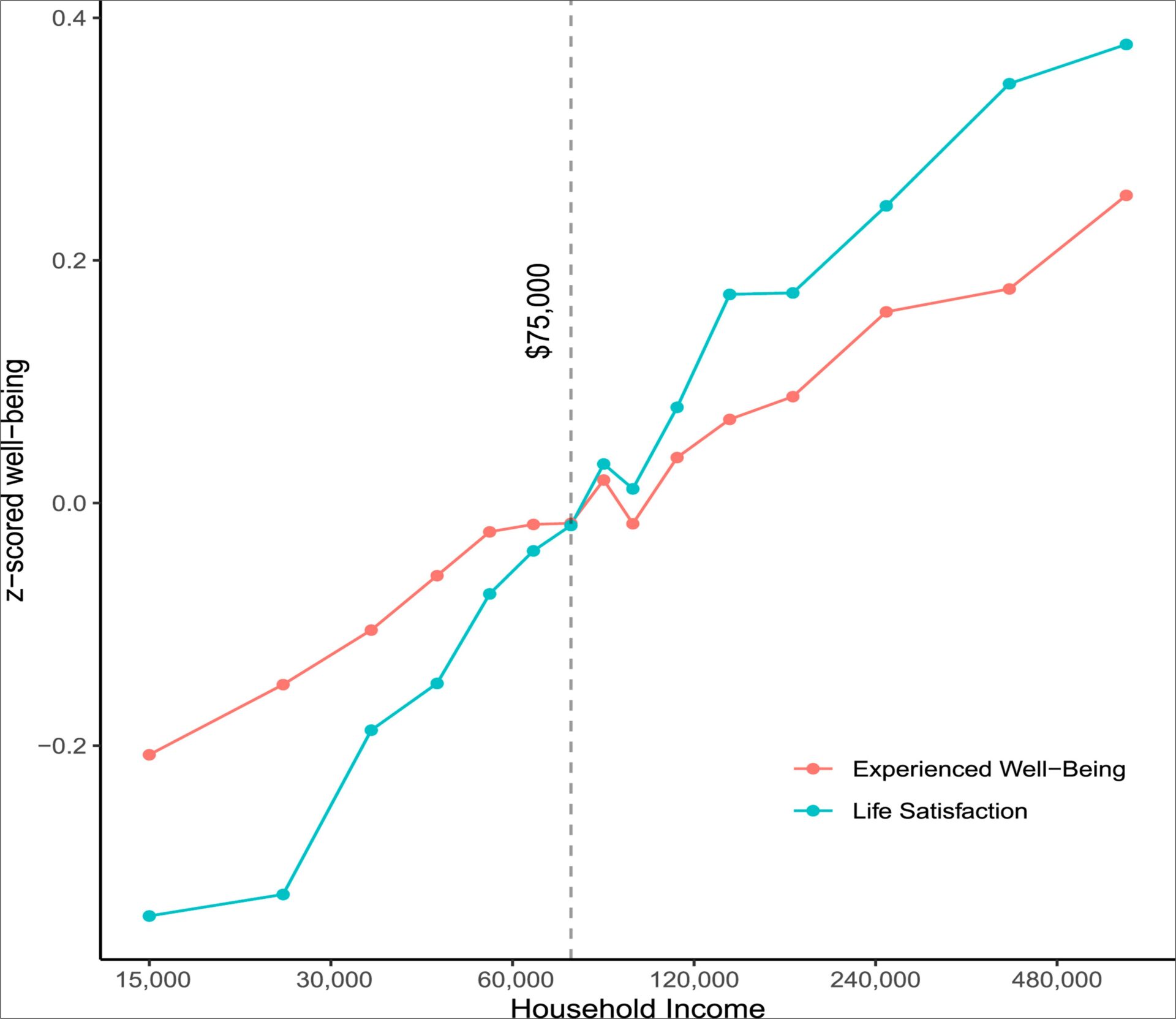

What is the relationship between money and well-being? Research distinguishes between two forms of well-being: people’s feelings during the moments of life (experienced well-being) and people’s evaluation of their lives when they pause and reflect (evaluative well-being). Drawing on 1,725,994 experience-sampling reports from 33,391 employed US adults, the results show that both experienced and evaluative well-being increased linearly with log(income), with an equally steep slope for higher earners as for lower earners.

There was no evidence for an experienced well-being plateau above $75,000/y, contrary to some influential past research. There was also no evidence of an income threshold at which experienced and evaluative well-being diverged, suggesting that higher incomes are associated with both feeling better day-to-day and being more satisfied with life overall.

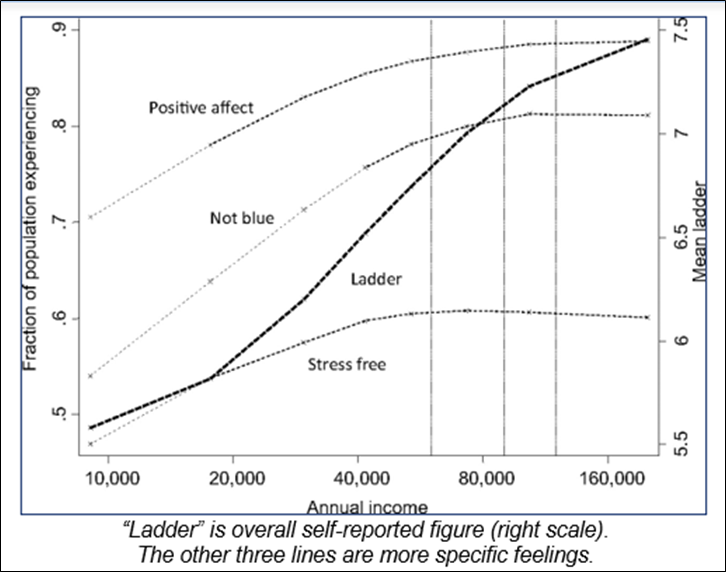

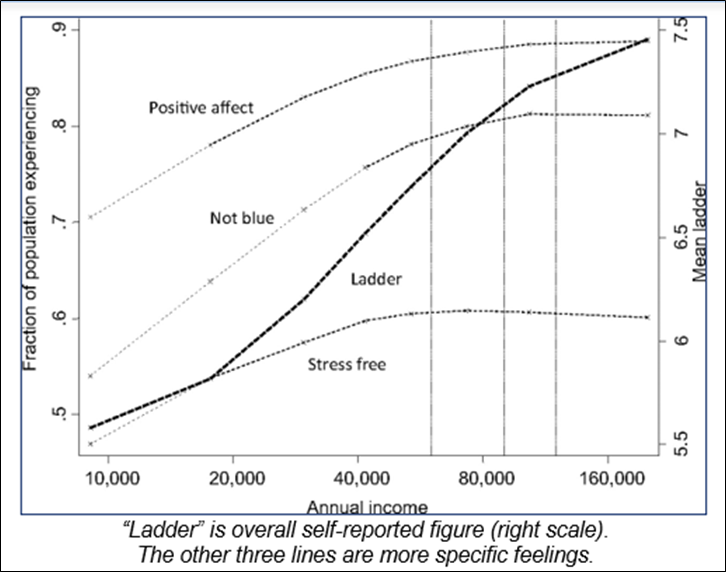

First of all, the $75,000 number referenced is from a study done in 2010. The inflation-adjusted number would be closer to $100,000. The study (by Kahneman and Deaton) is here. It’s good; definitely worth a read. The Kahneman / Deaton money vs. happiness curve looks like this:

Killingsworth’s key differential point is that the money vs. happiness curve does not flatten out (using log x-axis). There is nuance in the two studies, but the two charts tell the main story. The Kahneman one is here and Killingsworth’s is below:

Mean levels of experienced well-being (real-time feeling reports on a good–bad continuum)

and evaluative well-being (overall life satisfaction) for each income band. Income axis is log transformed.

Figure includes only data from people who completed both measures.

Note that both charts use log for the x-axis; increased income has a diminishing impact on happiness. This is all superficially interesting and maybe it’s useful to know the aggregate or average relationship between money and happiness within a country or society. On the other hand, I think this is a bit like when you put one foot in a freezing cold bucket of water and one foot in a boiling hot bucket of water and take the average. Sometimes averages don’t mean much.

The only thing that matters to me or to you is the shape of our personal money/happiness curve in isolation. The shape and slope of an individual’s money/happiness curve is determined by many factors including the person’s ambition, values, and morality, plus their cost of living, social status, number of children, and so on. The aggregate curves don’t matter much or mean much at all.

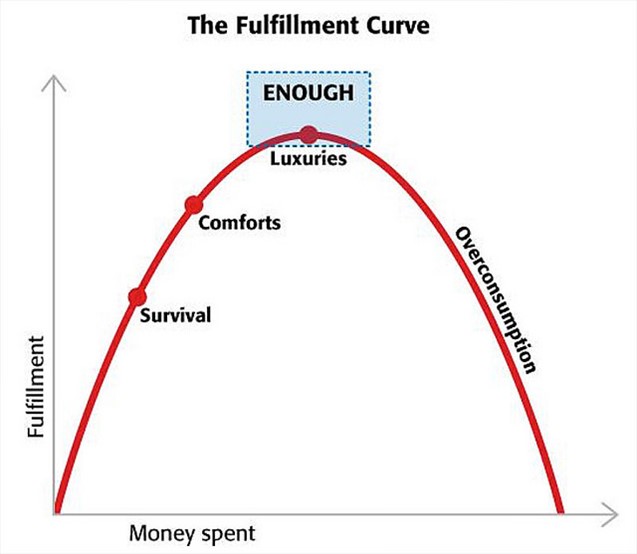

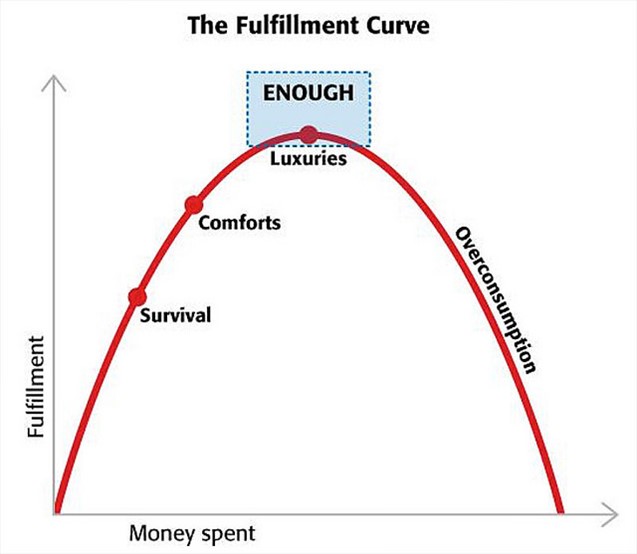

I have always been interested in the empirical relationship between money and happiness because I think it’s a topic that is underexamined in a world where we are pathologically driven towards overconsumption by various societal forces. With advertising, societal norms, social media, consumer culture, and even friends and family often pushing us to “succeed” in ways measured on a financial scoreboard, it’s important for each individual to understand the shape of their own money/happiness curve and pursue what they want, not what society says they want.

North American society in the 1980s was blatantly materialistic and few asked “how much is enough?”

Restraint and anti-consumerism are more in the zeitgeist now as the world is less materialistic than it was back when I was growing up. The 80s were a time when debaucherous, over-the-top hair bands like RATT and Mötley Crüe were Top 10 radio, Gordon Gekko was an idol, and bumper stickers and front plates like this one were displayed unironically.

A tactic that can help you survive the still-relentless onslaught of advertising and its worrisome ability to plant pointless desires in your subconscious mind, is to spend time thinking about the shape of your personal money/happiness curve. This will help you stay off the hedonic treadmill that makes us instinctively strive for more and more money.

From Wikipedia:

The hedonic treadmill, also known as hedonic adaptation, is the observed tendency of humans to quickly return to a relatively stable level of happiness despite major positive or negative events or life changes. According to this theory, as a person makes more money, expectations and desires rise in tandem, which results in no permanent gain in happiness. Brickman and Campbell coined the term in their essay “Hedonic Relativism and Planning the Good Society” (1971). The hedonic treadmill viewpoint suggests that wealth does not increase the level of happiness. Subjective well-being might be largely determined by genetics; that is, happiness may be a heritable trait

How money has shaped my life

I grew up in a lower middle-class family, in the second house from the top in this row of five attached houses.

Photo circa 1980-something, courtesy of the Donnelly Archives

We had enough money to live normally and not worry about cash but when there was a school trip to Europe or whatever… No chance. There was no extra money, just the necessary amount.

Meanwhile, my godparents successfully created and sold an advertising agency and retired when they were 40 years old. They had one child, and to keep her company (she was my age), they used to take me on their two-week-long trips to the Caribbean every March. While flying to the Caribbean in 2022 is a mainstream, middle-class activity for many, it was the height of luxury in the 1980s. Average families weren’t whipping off to the DR back then[1]. I got to see a whole different world of opportunity and awesomeness. “I want that!” I thought.

A fridge with a button you can press to get water!??! I want that!

A basketball hoop and net, right on your driveway? I want that!

The goal was to get out of suburban Ottawa and into something exciting and new and that had a huge influence on me as I viewed money as a key that could unlock freedom and novelty. The dream of big Wall Street money kept the fire in my belly all through high school and university. My high school years were the days of Gordon Gekko and Wall Street (the movie) and after I read Liar’s Poker cover-to-cover at age 15, I knew what I wanted to do. My one and only goal was to become a trader on Wall Street[2].

I had a crystal-clear and laser-focused motivation: money. That singular focus was good.

However, as I matured [cough cough] and built a decent life for myself and my family, money became less important. There is a minimum level everyone must reach before they can stop worrying about money. Above that amount, the correlation between money and happiness drops off. For most people, it flatlines at some point. For me, that point is not all that far up the y-axis.

The key question to answer clearly and honestly is: What does your money/happiness curve look like? Is it curved or linear? Does it flatline somewhere? If so, where?[3]

The naïve and single-minded pursuit of a high-paying job when I was young made my life pretty simple. I had one clear goal and all I had to do was work towards it. The weird thing about dreams though, is that once you achieve them, there is a hole where that dream used to be. For many, including me, achieving a dream can produce a fleeting sense of elation followed by a deeper existential vertigo as the thing that was pushing you forward all those years slips away into the void. All that’s left is a feeling of: now what?

By the time I hit my 30s, I had a good sense of my money/happiness curve, and I could see that it got flat, fast. I realized that any increase in money would not give me much new freedom or happiness and I hit a bit of an existential wall. My motivation was no longer clear or obvious. I still sometimes have tricky thoughts about what I’m doing here still trading at age 49 when there are so many other interesting things to do out there in the world. My early-life focus on money meant I needed to find new reasons to trade as I got older.

After looking inward and thinking about things for a few years, I grew into a new set of motivations.

- I love trading. I enjoy going to work every day. Going into an office where I enjoy what I do, I like the people I work with, and I respect the management I report to, have been the most important drivers of my professional happiness over the years. The constantly evolving macro picture and the ever-changing market regimes and nearly impossibly complicated process of trying to solve the market is enjoyable. If you enjoy coming into work each day, the money doesn’t matter as much. No job is fun all the time, but if trading isn’t fun most of the time, you’re not doing it right.

- I want to publish my writing. One of my favorite things to do is write about finance and markets. Working at a credible financial institution like Spectra and writing AM/FX every day is the best way for me to do that. Again, intellectual stimulation before money.

- I want to maintain my current level of financial success but do not particularly aspire to anything more than what I have now, financially. The idea of getting super rich does not make my heart beat faster. I plan to be thankful and keep doing what I do until the day they tap me on the shoulder or the day I don’t love it anymore. Until then, I am grateful for the job I have, and I don’t need to dream of making 10X what I’m making now. I know that will not make me happier.

Don’t be one of those people that just always wants more. That will put you on the hedonic treadmill, running towards a meaningless goal that is forever out of reach. Be thoughtful about what kind of money you need to do what you want to do and aim there. Don’t keep moving the goalposts. More money is not always the answer. In fact, more money is often not the answer, unless you are struggling to pay rent or cannot afford to pursue specific, costly passions like travel or owning a boat.

Now, let’s bring this all back to trading.

Ill-gotten gains? How money morals matter in trading

I just found a million dollars that someone forgot

It’s days like this that push me o’er the brink

– Guns ‘n Roses, Pretty Tied Up, 1991

So far, this piece is about the broader question of money vs. happiness. Now, let’s connect the dots to trading.

Think about your history (childhood and young adult years especially) and how it might influence your trading performance. For example: if your dad was an electrician and your mom was an entrepreneur… Your subconscious might have trouble with the idea that in trading you magically pull money out of thin air without any traditional hard work and without producing or creating anything[4]. You might find your subconscious repeatedly sabotages you in an effort to divest what it perceives as ill-gotten gains.

Many traders from blue-collar families struggle with this when they first find success. It is a strange and sometimes surreal feeling to generate huge income without producing anything. Trading is not the only job where this is the case, but the sometimes sudden and gigantic income streams from trading make it different from most other professions.

Believe it or not, there is more to life than trading. Think about the long game and your entire career. While it is fun to trade all night and live a fast and exciting life, you cannot do that forever. Trading on its own does not offer a path to happiness, no matter how much money you rake in. Financial freedom is one facet of happiness. Most research shows true happiness comes from: Health, relationships, family, friends, and a feeling of purpose.

While it might feel like your P&L ups and down are a matter of life and death—they are not. Traders spend way too much time thinking about P&L and money and all the things it might mean to them. Focus on trading when you are at work and focus on relationships and activities you love when you are not.

A life of trading is a life full of hills and valleys. Every time you lose more money than you ever have before, it hurts. Right in the gut. And every time you make a new “best day” or hit your lifetime high water mark, there is a giddy sensation that is hard to regulate. If you are a good trader, you will trade with more and more capital and bigger positions as the years go by and therefore by definition your biggest up and down days will get bigger and bigger over time.

Some traders (including me until about 6 or 7 years ago) are afraid to feel happy after a great day or a great trade because they don’t want to jinx themselves. This creates an asymmetry where you feel bad after the bad days, but you don’t give yourself permission to feel good after good days. Over the years, this can be incredibly draining because you only let yourself feel the bad emotions.

If you have a good day, feel good about it. Be happy. Go celebrate. Order the Château d’Yquem. But don’t celebrate until you have taken profit! Celebrating while in a winning position is a recipe for disaster. Take profit, then go be happy.

As time goes on, you should be able to figure out how to manage your emotions so that while your P&L is making higher highs, your emotions become less volatile. You recognize after a while that no matter how bad the day, or how bad the loss, you don’t die. It might feel like you are going to die, but you don’t. The only way to learn this is to experience mind-numbing losses. As my boss once told me after a particularly bad day of trading: You don’t learn anything when you win. Every loss is a lesson.

Always remember…. Hills and valleys. Hills and valleys. Don’t let yourself get too high or too low. Regardless of your P&L, the sun will still rise tomorrow, your kids will still love you and even in the most extreme situation where you end up losing your job as a trader, life STILL goes on.

At the end of the day… It’s only money.

Notes

[1] Dominican Republic tourist arrivals today are around twenty times what they were in the early 1980s.

[2] Not exactly true as I wanted most to be a major league infielder. But that was more of a dream than a real goal. I didn’t work hard enough or lift weights or do the things necessary to become a professional baseball player. On the other hand, I did do everything possible to become a trader. I still remember a Lehman Brothers recruitment brochure from 1993 that featured this Q&A with a senior trader: “Q: Why did you decide to work at Lehman Brothers? A: Because I wasn’t good enough to play for the New York Yankees.”

[3] Some people also have hump-shaped money/happiness curves.

[4] Sounds a lot like MMT. :U