August 11, 2023

Camp Kotok

I was back at work for just one day after Camp Kotok and then I got slammed by COVID… I’m still out sick, but should be back Monday. Here I am, though, trying to at least produce one last am/FX this week. Today: my takeaways from Camp Kotok in Maine.

What is Camp Kotok? Camp Kotok is a gathering of prominent economists, policymakers, central bankers, traders, asset managers, and journalists¹ that has taken place every August for more than 20 years. It is part economics conference, part debate-o-rama, and part summer camp for adults who like to fish, drink, and play poker.

Overall vibes on the economy were… Confused. Some economists have abandoned recession calls while others remain steadfast. The word “reacceleration” was heard a bunch as some feel the manufacturing cycle will bottom soon, despite bad real-time data on China exports, German PMIs, and global trade in general. I suppose the best two-word summary of the mood is: Reluctant optimism.

I feel there is a cohort that will simply continue to predict recession until it finally hits, because switching costs are high when you are an economist… But those predictions have been costly so far. This cycle has been a reminder that the recession prediction signal from the yield curve is basically useless given the unknowable lag before impact.

Outside of steadfast recession predictions, another narrative strongly in the mix (and the narrative which the core of the Fed is embracing right now) is immaculate disinflation. The scenario where the Fed lands the plane on the Hudson, Sully-style, and unemployment ticks marginally higher as CPI tumbles back to 2%. That’s possible!

To give you a sense of how impossible this year has been for forecasters, here are 23 narratives forecast by reasonable people at some point in 2023.

- US hard landing and recession

- US soft landing

- US no landing, re-acceleration

- NEW! Immaculate disinflation leads to Fed cuts in 2024

- China reopening and consumption boom

- China slowdown and disinflationary balance sheet recession

- Inflationary boom in Germany and Europe

- Export-driven recession in Germany on peak global trade

- UK stagflation

- UK resilience

- Regional bank crisis in the US may signal end of US hegemony

- Fed could cut 50 and end QT at March FOMC

- Fed’s gonna cut in July

- Fed’s gonna hike in July

- OPEC production cuts will take oil back up through the highs

- OPEC doesn’t matter, they have lost control of the market

- Fed hikes will break something

- NEW! Fed hikes are stimulative

- US debt crisis

- USDJPY will go lower on BOJ changes to YCC

- USDJPY will go higher on BOJ changes to YCC

- AI will usher in a new era of productivity

- AI : Humans… as… Humans : Gorillas

It has been the trickiest of years for macro prognostication and for economists’ forecasts in aggregate. Meanwhile, most attendees in Maine nodded in strong agreement after one economist said the Fed still has no working model that begins to explain inflation.

“We are data dependent!” can be an empty statement when you have no working model of inflation. This can lead to a situation where you proclaim you’re data dependent in June, then inflation comes in lower and the jobs data comes in weaker than expected… And you hike in July.

More on this topic: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/monetary-policy-without-a-working-theory-of-inflation/

A simple empirical scan of the last 20 years would suggest that monetary policy influences asset prices and procyclical fiscal policy influences consumer prices, but there is a sample size issue and there is a confounding variable: COVID shut the entire world down. So we still don’t necessarily have a working model of inflation, though the MMT framework has gained some credence over the last three years. By creating a shortage of goods and workers, sufficiently large fiscal policy appears to have the power to drive up wages and consumer price inflation. Maybe. Then again, Europe did less fiscal and got more inflation. Economics is hard.

I have a theory that markets are a complex system like the weather. With given starting conditions and some reasonable model of how the world works, you can potentially predict the next 3-10 days with greater than 50% accuracy. After that, there are so many paths in the Monte Carlo simulation, and so many new variables that you don’t even know to include in your process… It becomes impossible. Obviously my theory fits my trading time horizon (so I could be biased toward believing it), but I think books like Superforecasting also support the idea that multi-month and multi-year forecasts in highly complex systems are close to impossible.

You can reasonably guess what variables will matter over the next few days and assign a certain level of directional skew and variance to the outcomes (e.g., economic data points, central bank meetings, cross-market events like OPEC, etc.) but if you try to do this out six months… It’s too hard.

—

¹ And me.

Do Deficits Matter?

The day before I left for Maine, I wrote a piece called “am/FX: Unhinged” which detailed the unprecedented and wildly procyclical nature of US fiscal deficits since 2017. As any regular reader knows, I tend to yawn when people talk about US debt and US deficits and the end of the dollar, but I will admit that my confidence in America’s ability to avoid some sort of debt crisis in the next few years is no longer anywhere near 100%. We are in a world where revenue has become irrelevant to spending plans, even when the economy is on fire. Fiscal numbers are so large as to be incomprehensible. No human being can grok what a trillion is. Or five trillion.

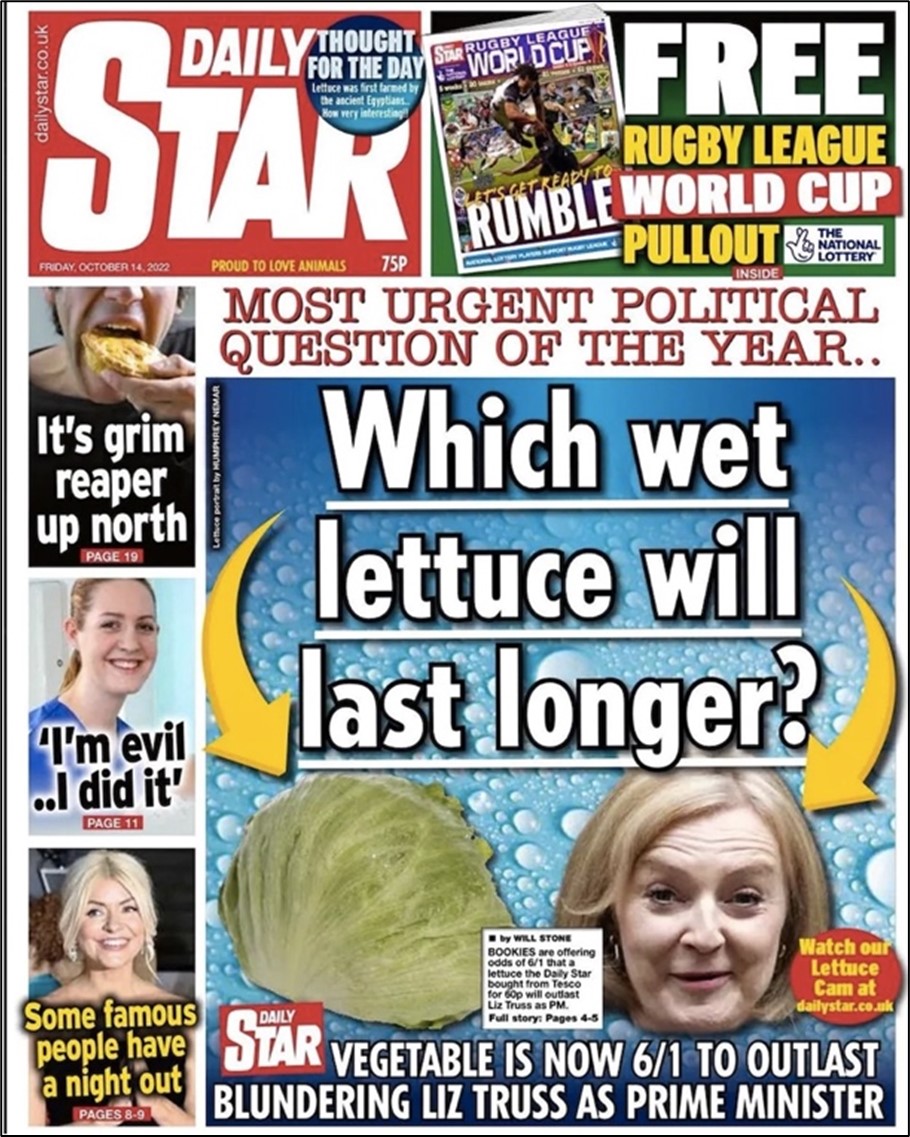

The Truss / UK blowup in September 2022 is the template I would imagine for a return of the bond market vigilantes to American markets. My best guess for a catalyst would be that on the next ginormous fiscal spending announcement, the bottom simply falls out of US bonds. It’s the kind of thing that could happen anytime, really, but the market has come to terms with the most recent CHIPS and Science Act and while the Fitch downgrade is a reminder of the increasingly-scary fiscal situation, my guess is people forget about the downgrade sooner rather than later.

The timing of the Fitch downgrade obviously made it salient at Camp Kotok and this probably partly explains why US deficits were such a big topic of discussion. There is no precise limit to how much debt a country can accumulate, and there is no barrier to creating money to fund higher interest costs. But what’s new in the last six years is the total disregard for the question of: “How are we going to pay for it?” That question is irrelevant until the bond market truly freaks, as it did in the UK… And then politicians’ incentives change overnight.

Presumably, any sort of bond market freak-out will be met not just with some less-aggressive fiscal stance, but also with massive intervention by the Fed. That will restore the floor in UST prices, weaken the dollar, and probably punt the crisis forward a few years. I say this, but the UK intervention was bullish GBP because of the mechanics of the short gilts / short GBP trade. So the currency impact is not 100% certain—starting point will matter.

Anyway, this is fun to write about, but not yet actionable. The reason I’m writing this out is that it’s something you want to be ready for so you know it when you see it. Let’s take a look at what might be a warning sign: Massive, decorrelation of the USD and US yields. In other words, bonds down / USD down. Much as Truss faced, gilts down / GBP down. That is the textbook market reaction in an EM fiscal crisis and that’s why people were joking in 2022 that “UK is the new EM.”

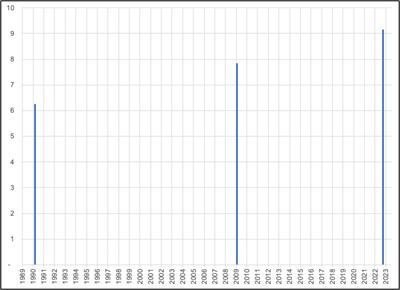

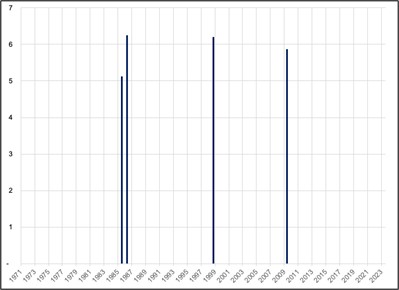

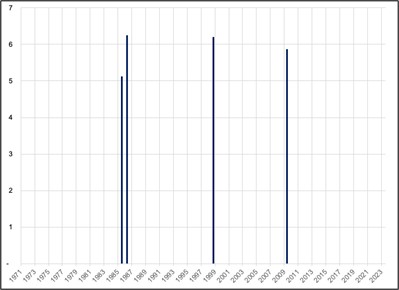

I looked at the UK, USA, and Europe and simply asked Excel to show me any time bond yields moved up more than two standard deviations in the same week that the currency dropped more than two standard deviations. This should be rare given the positive correlation between G10 FX and nominal yields. Let’s start with the UK.

Weeks where gilt yields up 2SD, and GBPUSD down 2SD (y-axis is total SD of both moves added)

This situation of yields up 2SD and currency down 2SD has happened in the UK three times since 1989. The first was a repricing of GBP on ERM jitters, the second was when the UK bailed out the banks in 2009 (and the market wrongly saw that as bad news for the UK). Here’s a fun quote from the 2009 episode:

…Notable American investor Jim Rogers, co-founder of the Quantum Fund, said the British sterling, plunging in value, was a lost cause.

“I would urge you to sell any sterling you might have. It’s finished,” Rogers said.

That’s a classic example of how asset prices don’t make lows on good news. GBPUSD went straight up after that.

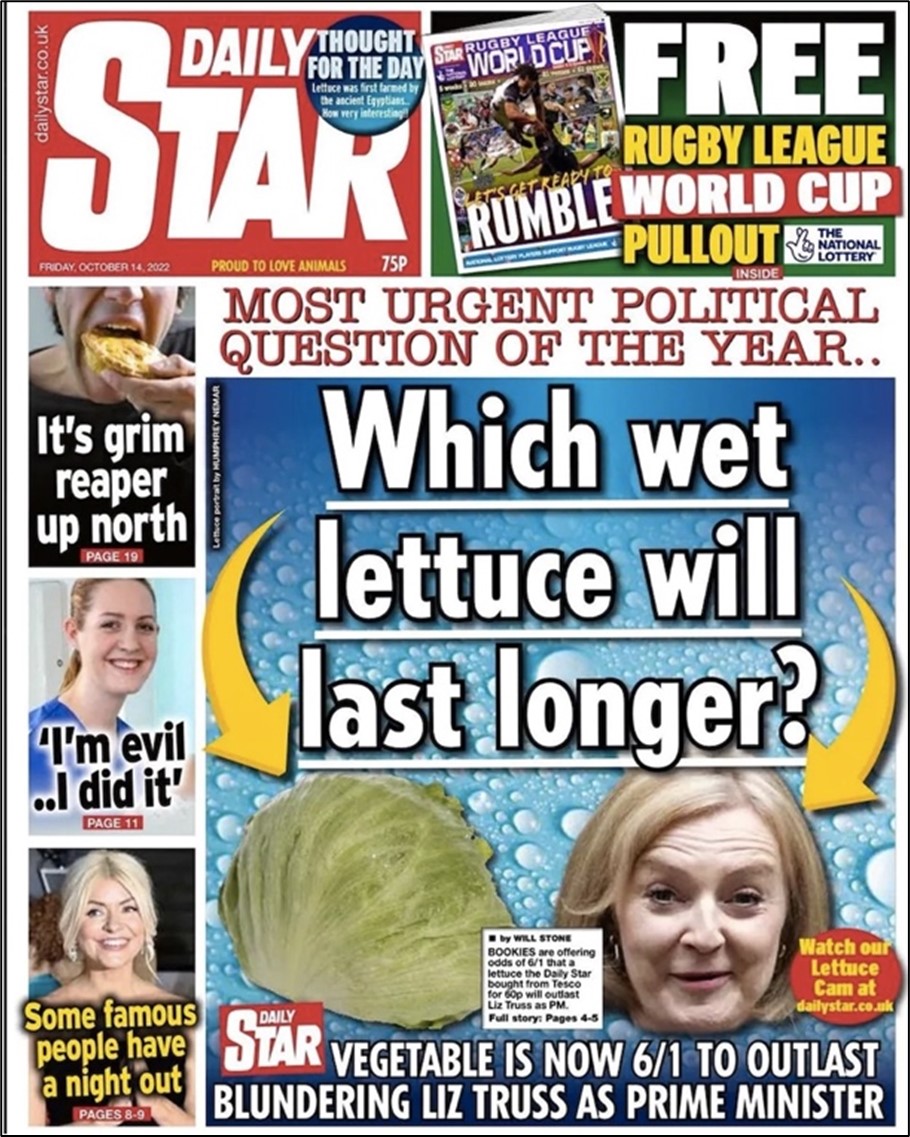

The third incident of yields up / currency down two standard deviations, of course, was October 2022 when gilts and GBP cratered on extreme skepticism around the Truss mini-budget. This was an escalating exit from gilts and GBP in response to unfunded tax cuts and energy bailouts. A week later, the Bank of England intervened in the bond market and there was a rapid fiscal policy reversal as Truss fired Kwarteng and her tenure as PM lasted about as long as a wet head of lettuce. Stability was soon restored.

Next, let’s look at the USA.

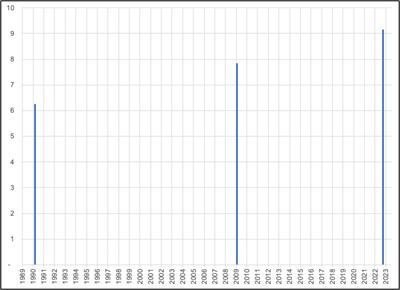

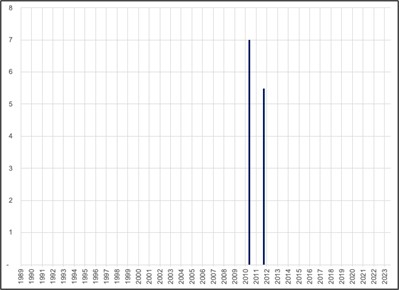

Weeks where US10y yields up 2SD, and DXY down 2SD (y-axis is total SD of both moves added)

The first two bars on that chart are in 1985 and 1987. This is the period immediately after the term “bond vigilantes” was originally coined by Ed Yardeni in his July 27, 1983 newsletter. He said:

Bond Investors Are the Economy’s Bond Vigilantes. If the fiscal and monetary authorities won’t regulate the economy, the bond investors will. The economy will be run by vigilantes in the credit markets… Of course, bond investors don’t have regulating the economy in mind but are simply acting in their perceived financial best interest—i.e., out of rising and falling concern that inflation might erode the effective purchasing power of their bond investment returns.

The 1980s were a wild time for financial markets as Ronald Reagan took the US into net debtor status for the first time on the back of massive tax cuts and higher Cold War defense spending. While Reagan promoted a narrative of fiscal conservatism, the reality was something else. Interest costs were high and defense spending was high, and recession forced government spending, while tax cuts reduced revenue. 1985 to 1987 saw a lot of articles like this one:

LA Times: US becomes net debtor for first time

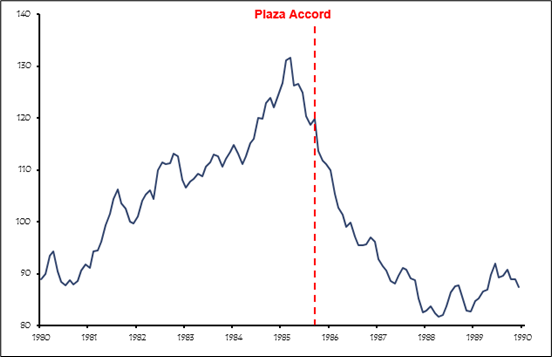

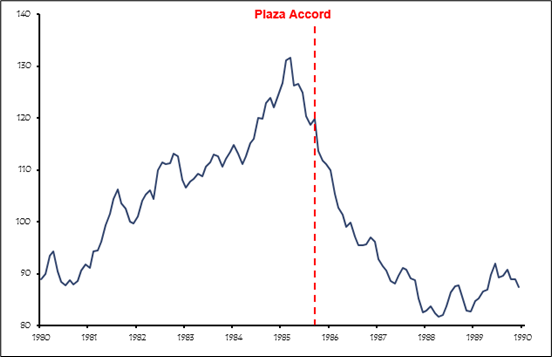

And of course, the National Debt Clock went up in the 1980s too. While concerns about the national debt were front and center, the Plaza Accord was also unleashing the biggest symmetrical mean reversion trade of all time in the US dollar. Concerns about the unsustainable debt and the success of the Plaza Accord triggered those two bond vigilante moments in 1985 and 1987.

USD Index around the Plaza Accord

The next bar on the chart (where the USA had a simultaneous weekly move 2SD up in yields and 2SD down in the dollar) was October 1998. That was not a bond market vigilante moment, it was LTCM unwinding bond arbitrage bets at the same time as G7 USD-selling intervention in USDJPY. As bonds were being sold willynilly by the failing geniuses at LTCM, USDJPY collapsed from 148 to 114 in two months. Absolute carnage. The Fed arranged a bailout of LTCM and in a surprise intermeeting move, cut rates a week later. Stability was soon restored.

The final appearance of a bar on that chart was the sharp fall of the dollar and rise in yields in May 2009. Again, this was not the bond vigilantes, it was simply raging “risk on” markets as China stimulus, global banking rule changes, and a return of confidence led to a massive rally in equities and commodities, and a drop in bonds and the dollar. This was a good news move, so no central bank intervention on this one.

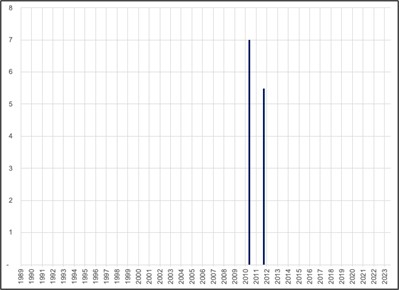

Now let’s look at Europe. I’m using Greek yields as they are most sensitive to bond market concerns about debt.

Weeks where Greek 10y yields up 2SD, and EUR down 2SD (y-axis is total SD of both moves added)

This one is pretty obvious. EURUSD and Greek yields went bananas a couple of times in the Eurozone crisis. The first one coincides with massive (and violent) anti-austerity protests in Greece (not to mention the US Flash Crash was that week). A week later, the ECB announced its unprecedented bond buying program.

The second incident was early September 2011. In the next two weeks, the SNB put a 1.20 floor under EURCHF, and the Bundestag agreed to a much more aggressive bailout of weaker Eurozone partners. The crisis continued for another 10 months until Mario Draghi’s magic “Whatever It Takes” speech in July 2012.

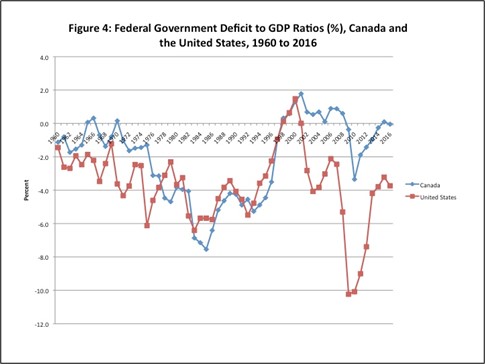

The bond vigilantes also showed up in the 1990s in both Canada and the USA but the bond market moves and government reactions were more glacial and ran from 1992 to 1998 or so. This is a good timeline of how Canada mollified the bond vigilantes in the 1990s.

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-crisis-timeline/timeline-how-canada-tamed-its-budget-crisis-idUSTRE7AK0FF20111121

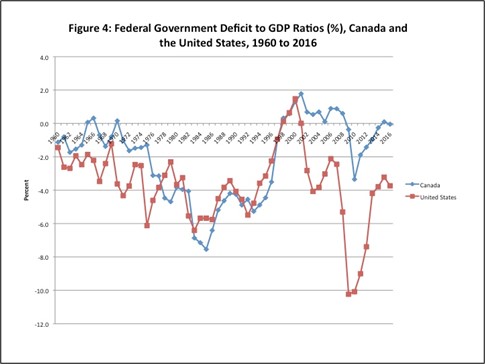

In both the US and Canada, yields appeared to be rising more on concerns about deficits than on hopes for higher growth. In response, Canada and the US both took aggressive measures to get the budget back in balance. In the chart at right you can see the aggressive increase in deficits during the Ronald Reagan and Brian Mulroney administrations and then the return to balance engineered by Clinton and Chretien in response to changing political incentives (and the end of the Cold War).

So the lesson here is that when bonds and the currency both fall two standard deviations in one week, government intervention is coming. Every single time. Any sort of US bond market crisis driven by fiscal concerns is likely to be an ongoing battle between markets selling bonds and the Fed buying them back. As we saw in 2008 (US), 2012 (EU), 2015 (China), 2020 (everywhere) and 2022 (UK)… The authorities always win. It might take a while, but they always win.

But that doesn’t mean you can’t make money in both directions.

One final note on the US deficit story. The 2024 election and the policy announcements afterwards (in 2025) could be a flashpoint. David Kotok pointed out that US 1-year CDS have come all the way back down post-debt-ceiling resolution while 5-year CDS came off somewhat, but not as much. Here are the charts:

US 1-year CDS all the way back down…

…5-year, not so much

AGI

Each night before dinner in Maine, there is a one-hour debate or conversation of some sort about a topic in the zeitgeist. Friday, the topic was AI and AGI. The conversation was led by Dave Nadig, Sam Rines, and Jim Bianco. A few points I found interesting:

- Sam thinks AGI could provide enough of a productivity boost in developed markets to offset the demographic slump. As the workforce becomes more productive, this will reduce stress and shortages in the jobs market, even as the working age population peaks.

- Dave referenced Stuart Russell a few times. Russell is an AI expert, professor of computer science at UC Berkley, and author of “Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control.” He has been writing about AI since 1995. Here is a useful excerpt from “Human Compatible.”

“It doesn’t require much imagination to see that making something smarter than yourself could be a bad idea. We understand that our control over our environment and over other species is a result of our intelligence, so the thought of something else being more intelligent than us – whether it’s a robot or an alien – immediately induces a queasy feeling.

Around ten million years ago, the ancestors of the modern gorilla created (accidentally, to be sure) the genetic lineage leading to modern humans. How do the gorillas feel about this? Clearly, if they were able to tell us about their species’ current situation vis-à-vis humans, the consensus opinion would be very negative indeed. Their species has essentially no future beyond that which we deign to allow.

We do not want to be in a similar situation vis-à-vis superintelligent machines. I’ll call this the gorilla problem – specifically, the problem of whether humans can maintain their supremacy and autonomy in a world that includes machines with substantially greater intelligence.”

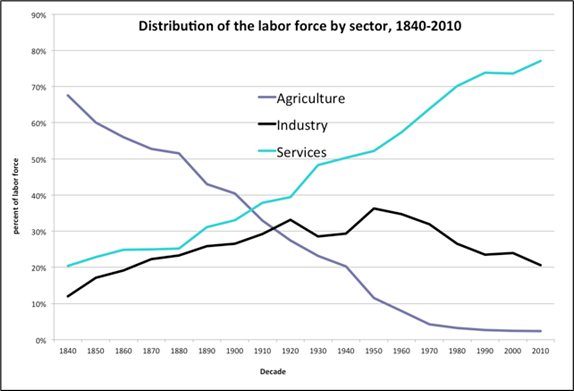

- Most everyone waved off the threat to human jobs posed by AI as we have seen throughout history that new technologies create more jobs than they delete. The anxiety comes from the fact we can easily see what jobs a new technology will take away, while we cannot imagine the new and exciting jobs it will create.

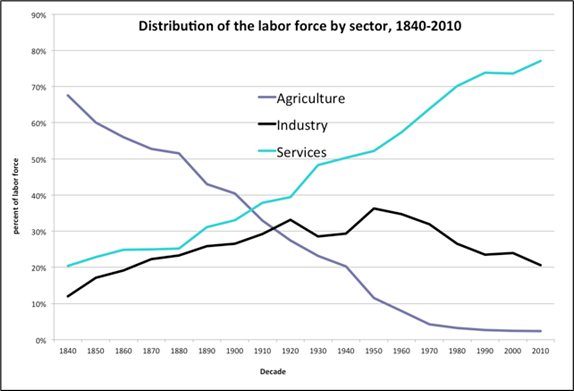

Technology and the passage of time eliminate some jobs and create others

- There was some discussion over whether it’s the US or China that has an advantage in AI. While the US holds the technological advantage, an autocracy with infinite human testers and potentially fewer ethics hurdles could also have advantages. Tie.

- Finally, there was some discussion about whether current LLMs will run into copyright violation issues at some point as they are simply regurgitating / parroting / aggregating billions of words of copyrighted material. Will they accidentally spit out passages that lead to lawsuits?

Final Thoughts

There were a bunch of other debates and conversations that have some relevance to readers, but I’ll cut things off here as this is 3000 words, and that’s a lot. I will cover a few other Camp Kotok topics over the course of next week.

Finally, some bonus reading on how bond vigilantes create lower inflation.

Have a healthy weekend.

good luck ⇅ be nimble